(Bloomberg) — Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo warned that US efforts to build out the domestic semiconductor industry could be delayed by years if companies are required to go through standard environmental reviews, signaling climate regulations may clash with national security goals.

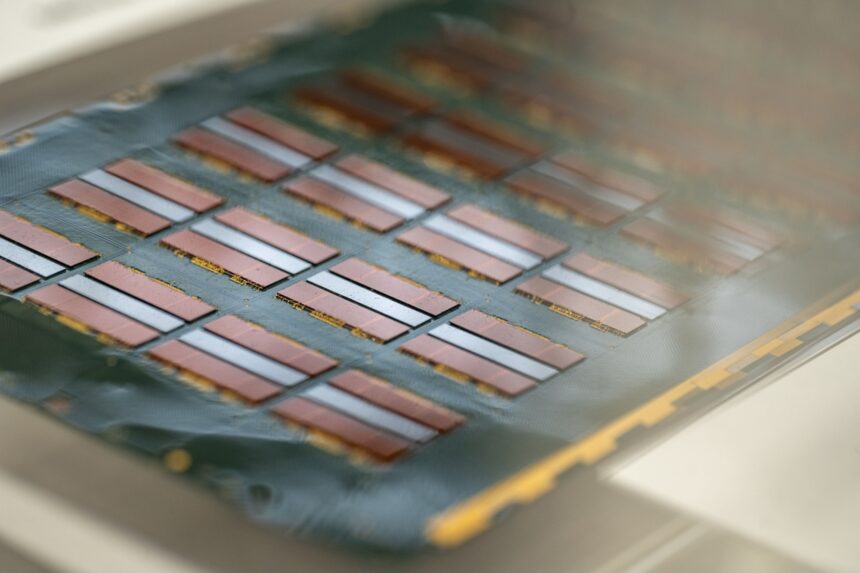

Projects under construction by Micron Technology Inc., Intel Corporation, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company – who’ve together pledged up to $195 billion in US investment – are among those that could be affected by lengthy reviews that Raimondo and a bipartisan group of lawmakers had tried to avoid.

Raimondo in October urged Congress to approve a measure exempting federally-funded chips projects from such environmental permitting, which she said could force construction to stop for “up to years.” Asked whether that was still her assessment after House Republicans killed the exemption measure last week, she said “yes, potentially.”

“Obviously we want to do everything always to protect the environment,” Raimondo said in an interview with Bloomberg News in Nashua, New Hampshire. “But this is a national security priority, and we need to move quickly.“

The Commerce Department on Monday announced its first award from the 2022 Chips Act, which set aside subsidies worth $100 billion to revitalize domestic chipmaking and reduce reliance on Asian supply chains that Washington worries has left America vulnerable.

Over the next year, Raimondo said she expects to make as many as a dozen additional announcements – including to large advanced chipmaking facilities that cost tens of billions of dollars to build.

But those facilities also come with risks to the environment, as the semiconductor sector’s carbon footprint is set to double by 2030. They have water demands equivalent to small cities and can consume as much electricity as small countries. They also use process gases that drive greenhouse gas emissions, and rely on toxic so-called forever chemicals.

Chips Act applicants had to submit an A-Z environmental questionnaire to Commerce – and the vast majority of such projects that win funding will now go through permitting under the National Environmental Policy Act. NEPA is triggered by the amount of federal money involved, among other factors.

That review could force a lengthy construction stoppage at sites key to the US effort, which is already under significant pressure from Beijing as China races to build its own chipmaking capabilities.

Raimondo said Commerce has a small NEPA team that’s focused on streamlining the process for particular facilities, like TSMC’s in Arizona or Intel’s in Ohio. Commerce is also urging governors’ offices to designate a point person for state-level permitting, Raimondo has previously said.

“We’re gonna do everything we can to parallel process,” she told Bloomberg on Monday, including encouraging companies to staff up for NEPA review.

“That’s the single most important thing we can do – get the companies to hire consultants and lawyers,” she said. “The sooner you start, the sooner it finishes.”

Some companies have already begun the NEPA paperwork, she said, given that such reviews were always on the table if they received Chips Act subsidies. But they had hoped for a reprieve from Congress, particularly after the Senate overwhelmingly approved the NEPA exemption provision over the summer.

Manish Bhatia, Micron’s executive vice president of global operations, said of the measure that he’s “still hopeful that everyone wants this to happen.” Micron is building sprawling semiconductor sites in Idaho and New York, both of which have their own permitting regimes in addition to the federal process.

Leading artificial intelligence chip supplier Nvidia Corporation, meanwhile, said its supply chains are unaffected by last week’s permitting showdown. That’s because the American firm outsources production to companies largely based in South Korea and Taiwan.

Many environmentalist groups, meanwhile, consider NEPA to be a bedrock climate law and opposed a 2022 law that made semiconductor projects eligible for expedited review. Now, a new coalition of leading labor and environmental groups wants chipmakers to enter formal community benefit agreements that address a range of sustainability and other issues.

The coalition seeks a “baseline commitment to building the industry in a way that is far more sustainable than it was decades ago,” Sierra Club executive director Ben Jealous said in an interview — and “each year a commitment to evolving to become more and more sustainable.”